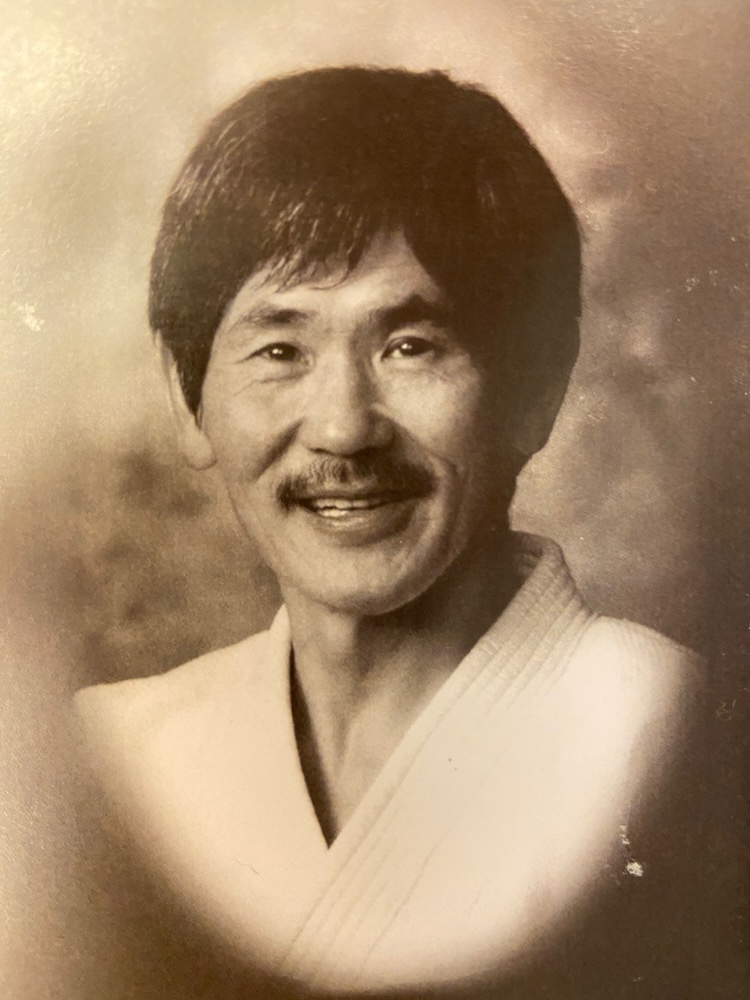

The Tokyo Roots

The life of Minoru Kanetsuka Sensei Shihan, began in Tokyo in 1939, laying a strong foundation deeply connected to the heart of Japanese martial arts tradition. His rigorous journey into the martial world started as a dedicated student at Takushoku University, pursuing Aikido intensively from 1957 to 1961. During these foundational university years, the young Kanetsuka was profoundly shaped by instruction from two distinguished masters: Gozo Shioda and Masatake Fujita, building his early promotions, including his Nidan, through the demanding standards of the Yoshinkan school. It is said that Masatake Fujita Sensei would become a very important figure in the life of this future Shihan. This intense period of study forged the disciplined spirit and deep dedication that Sensei would eventually share with the wider world.

Cultivating Aikido in Distant Lands

After graduating and laying his physical and mental groundwork, Kanetsuka Sensei embarked on a great adventure in 1964, seeking broader teaching experience across Eastern Asian countries. This journey cemented the practical nature of his approach. He spent a total of eight years across India and Nepal. In Nepal, he spent six years instructing Aikido to bodyguards attached to the royal household, gaining real-world application for his art. During this distant period, Sensei also ran a restaurant in Kathmandu for a number of years, demonstrating a versatile character that transcended the strict environment of the dojo. That experience might explain why Sensei liked to cook to his students in later years. Upon leaving Nepal, he continued his mission, moving to Calcutta, where he taught self-defense at a police training school. This immersion in practical instruction far from Japan provided him with profound experience, conditioning him for the powerful and influential work he would soon begin in the West.

Leadership and Enduring Influence

Sensei Kanetsuka arrived in Britain in 1971, or 1972, accepting an invitation from Kazuo Chiba Sensei to train at the Aikikai of Great Britain. His skills were quickly recognized; by 1973 he was awarded 3rd dan and made a Shidoin of the Aikikai of Great Britain, achieving 4th dan three years later. When Chiba Sensei decided to return to Japan in 1976, he personally nominated Kanetsuka Sensei as his successor. Following this endorsement, Kanetsuka Sensei assumed the mantle of Technical Director for the organization, which was renamed the British Aikido Federation (BAF) in 1977. This appointment officially designated him as the Aikikai Hombu representative in the UK. Sensei Kanetsuka’s influence quickly expanded across Western Europe. He devoted himself as the Technical Director for federations in Greece, the Netherlands, and South Africa. His commitment left an indelible mark on Norway, in particular, where he patiently served as the Norwegian Aikido Technical Director from 1977 to 1998.

The Distinctive School and the Fruits of His Labor

Kanetsuka Sensei dedicated his teaching to the absolute mastery of basic, orthodox Aikido principles, establishing a core philosophy grounded in practical, repeatable effort. His instruction, summarized in his repeated maxim, “Do basics and work hard,” pushed students toward true mastery.

He emphasized controlling an attacker from the first moment of contact with the “minimum of physical force”. This profound control later deepened under the influence of Sekiya Sensei, emphasizing atari, taking control precisely at the point of contact, achieved through a relaxed upper body and a strong center. Sensei instilled the rigorous practice of the traditional sword school of Kashima-shin-ryu, believing this serious weapons training illustrated how Aikido transcends reliance on brute physical strength. His vision demanded impeccable manners and adherence to traditional Japanese martial values, promoting the enlightened ideal that proper defense should also prevent injury to the attacker.

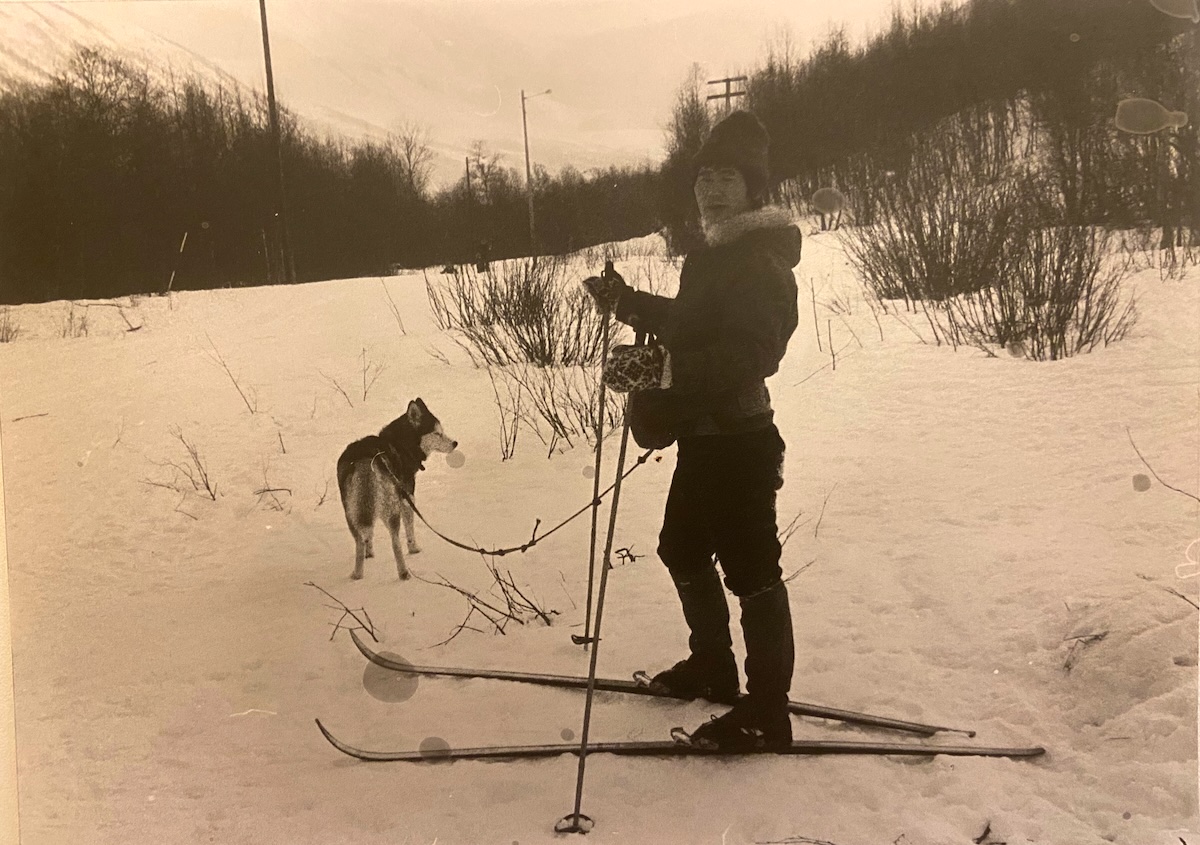

This core philosophy found its home at the Ryushinkan Dojos in London and Oxford. This name symbolized the reach of his teaching, extending abroad, such as in 1983 when Sensei officially conferred the Ryushinkan name upon Hubert van Ravensberg’s dojos in the Netherlands. His dedication bore lasting fruit in his students, especially Birger Sørensen sensei, a close student who immersed himself in Aikido and Za-zen practice at the London Ryushinkan starting in 1976,. Kanetsuka Sensei entrusted Sørensen Sensei deeply, frequently using him as his uke during this foundational period,. After training, Sørensen Sensei successfully carried the Ryushinkan ethos to Norway, opening the first Norwegian Aikido dojo in Tromsø in 1977 under Kanetsuka Sensei’s direct guidance,. These students inherited not just techniques, but the full, sincere weight of their teacher’s enduring martial commitment.

The Man Beyond the Mat

Sensei Kanetsuka was, simply put, unforgettable—not just for his technique, but for his commanding presence and profound humanity. When Peter Megann first saw him arrive at the Oxford dojo in 1973, he looked like a character straight out of a samurai film: massively built, with long hair, a curling mustache, a goatee beard, and wearing traditional wooden geta on his feet. Yet, beneath this striking martial exterior lay an amicable nature and a remarkable warmth. He possessed a fantastic memory for people’s names, once recalling a former acquaintance instantly at a course in Brussels, joking, “I didn’t recognize you. You used to have long hair”.

His sense of community extended to his personal life; while living in Oxford, he would host warm dinner parties for his students featuring the convivial “Mongolian pot” (where raw vegetables were cooked in boiling water surrounding a central chimney stack and served over rice or noodles). He was an adept cook, an enviable skill he honed while running a restaurant in Kathmandu for a number of years.

Students cherished moments where his deep martial wisdom blended with his love for life. Travelling abroad with him was always an adventure. On one occasion in Madrid, merely by scent, he located the exact tapas bar he had visited years earlier, exclaiming, “I can smell garlic prawns (gambas al ajillo)”. The owner instantly recognized him, confirming his enduring presence even across continents. His dedication was rooted in profound personal care for his students. At a major international course in Düsseldorf in 1985, when a confusing announcement left British students stranded without reserved accommodation, Kanetsuka Sensei insisted on leaving his own reserved hotel lodging to personally accompany his students to a sympathetic German student’s house to ensure their comfort and safety. The German students involved were astonished by this extraordinary level of concern. Above all, Sensei instilled the belief that Aikido transcends brute force; his ultimate, enlightened ideal was that proper defense must prevent injury both to oneself and, uniquely, to the attacker. He rigorously demanded adherence to traditional Japanese martial values and strict etiquette, ensuring students’ footwear was neatly lined up outside the dojo door, demonstrating that the discipline of the art started before they even stepped onto the mat.

Perpetual Legacy

Even during his greatest personal challenge, Kanetsuka Sensei demonstrated the unyielding spirit of a true budo master. In 1986, devastating headaches revealed a massive, far-advanced cancer. When given the grim prognosis by his physician, a former Aikido student named Kim Jobst, Sensei responded with extraordinary, serene composure and stoicism. His immediate, selfless reaction was entirely for others: seeing the worry in his doctor’s face, he calmly promised, “Kim, you look very tired. When I get better I’ll give you some shiatsu”.

Choosing fierce determination over comfort, he rejected heavy doses of morphine to endure constant acute pain, determined to keep his body functioning properly. He adopted a severe, cleansing regimen, converting to a 100% vegetarian diet and drinking prodigious amounts of carrot and beetroot juice. This sheer will was noted when visitors brought him sacks of carrots instead of traditional grapes and chocolates.

His dedication to the path remained absolute. Even when frail in the hospital, discussing ikkyo with a visitor, Kanetsuka Sensei demonstrated the technique, throwing the student to the floor with undiminished speed and vigor. After his release, the chemotherapy left him bald, and practicing in a tracksuit, he resembled a Buddhist monk in appearance. Shortly thereafter, fearing he might be perceived as too weak to lead an international course in Lille, Sensei insisted on attending,. Despite looking dreadfully weak and tired before the session, he gave a truly “revelatory demonstration” showing that Aikido “did not depend on physical strength,” effortlessly controlling a large, muscular French student. This commitment continued throughout his final years, leading to his well-deserved promotion to 8th Dan by the Aikikai Hombu Dojo in Kagamibiraki 2015.

Sensei Kanetsuka passed away peacefully on March 8, 2019. His students often speak of the privilege of observing his life, which was dedicated to constantly refining the art and continually finding new discoveries, treating the dojo as his laboratory. This vital legacy is carried on by his dedicated students, such as Birger Sørensen, Rex Lassalle, Hubert van Ravensberg preserving the orthodox principles he dedicated his life to teaching.